How to Select High Potential Projects

If you have limited budget, time, and resources—and who doesn’t?—then you need to focus. This precision is especially important for innovation leaders who are solicited by countless project teams. Here’s how I choose which teams/projects to sponsor.

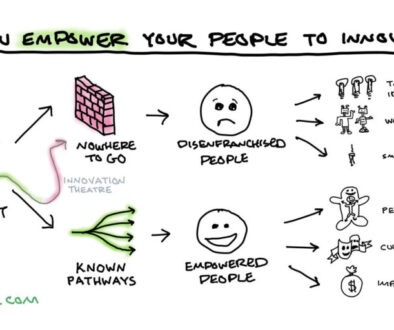

This post is part of a series on creating innovation programs. So far, I’ve shared:

- How to Create Innovation Events for Impact (Part 1)

- How to Create Pathways for Innovation in Your Org (Part 2)

This post addresses the next step: project selection. Don’t worry if you haven’t read the previous posts yet, because I wrote this article to stand on its own.

Leaders commonly ask me how to select projects for incubation and support. Here’s a model you can use.

What to look for in a project and its team

All projects need the right people to be successful, alignment to the company, and a large enough opportunity.

Each type of innovation needs a specific fit, (see How to Create Pathways for Innovation in Your Org for more on that), but all projects need to have the right People, Opportunity, and Alignment to have the best chance of success.

First, here’s what to look for in the people.

People

For People, you’re asking “Are they the right people for the work?”

The people part breaks down into these aspects:

- Are they passionate? All projects fail for the same reason: when the team stops working on it. So, you want the teams who are most likely to continue working when they encounter obstacles like rejection, life changes, or end of funding.

- Are they diverse? The more skills, backgrounds, and perspectives present on the team, the better they tend to deliver to their market. In his book Range, David Epstein goes into a lot of the science and anecdotes behind how people with diverse experiences often out-perform experts in new areas.

- Are they coachable? Are they fast, driven, and willing to try new and uncomfortable things to work differently? Most of your applicants have never incubated within a large company before. Most are veterans who are habituated to executing known business models. However, even startup experience doesn’t translate directly to an enterprise. You’re looking for lifelong learners.

- Is the team able to achieve this? Each team needs both the chops to do the work and representatives of the hacker, hustler, and hipster roles.

To assess these questions from behavior, you can use a hands-on application process to demonstrate that they can do the work. Provide training on the activities that you want them to do, then see who does them well. For new business style incubation, I ask the teams to do some customer development and size the market opportunity.

These activities have them do a lot of the leg work to help evaluate on Opportunity.

Opportunity

For Opportunity, you’re trying to identify if this idea will have the right impact at maturity and scale. This evaluation is tricky, but the idea is to reduce—not eliminate—uncertainty.

With that in mind, I have the teams research the answers to the below questions themselves:

- Can it be big enough? Does the back-of-the-napkin math work out that the market size can be large enough? It’s often hard to tell. In The Innovation Biome, Dr. Kumar Mehta presented this case study. At the time of the printing press, barely anybody could read. However, the printing press eventually expanded literacy to nearly the entire world. So, if you look only at the literate markets, you would pass on one of the most successful inventions in the world. To avoid this fallacy, look for teams to identify a passionate set of early adopters in a larger technology adoption curve.

- Have they found early traction? Although this will be rare if you look at early-stage projects, a growing number of users, customers, or stakeholders is an incredible sign. Traction shows that they have found something of value, have a compelling experience, and can hustle.

This next question is for you and the judging committee. It is less relevant if the traction is convincing.

- How obvious is the idea? Investor Peter Thiel famously asks entrepreneurs, “What important truth do few people agree with you on?” Obvious ideas are typically easier to see but harder to win. So, startups are often better off with non-obvious ideas, that big companies cannot convince enough people to try or move fast enough to win. And large organizations can often be successful with more obvious ideas due to advantages like advanced tech, leading market position, and lots of resources. For instance, hotel chains might never have pursued the AirBnB idea, but Marriott can buy Starwood, whereas a startup cannot.

This most recent reasoning starts to touch on Alignment. No matter the size of the opportunity, it’s moot if it does not fit your organization. It just won’t be adopted, or it will be shut down. So, let’s look more deeply into that.

Alignment

For Alignment, we’re asking: Would this fit for us? Here you want to balance between under-alignment and over-alignment.

The questions are:

- Is it aligned to our mission? Your organization probably has a strong mission statement. Does this ladder up to that?

- Does it use our strengths? For instance, a technology company probably wouldn’t acquire an ice cream chain.

- Does it align strongly anywhere? If a project aligns directly to an existing unit in your organization, seek early conversations with that unit to test alignment, and likely to seek sponsorship. This is usually a sign to pursue an incremental idea rather than a new venture. Teams that skip the alignment conversation risk cancelation if others see them as a distraction or—even worse—a threat.

If you have a well-aligned project, that will make things a lot easier for you to gain support and resources.

Now, let’s put it all together.

Conclusion

Putting it all together, look for projects that are the right mix of all three.

You can score all of these questions (I put 1-5) in a spreadsheet for all teams. That lets you see across the projects objectively. If you have a lot of applicants, you can be choosy and select for the best chances.

If there are fewer applications, then allow the first phase to be a test where they learn in the new job. If these projects don’t perform on their own, it’s better to cut them loose earlier and seek out better projects.

Either way, when scoring projects, perfect fidelity won’t be possible. The trick is to reduce uncertainty and keep things moving.

A metered funding approach ensures that you don’t overcommit to the wrong projects. Give a little support to a broad set of projects at first, then weed out the poor performers, and provide progressively more resources as projects earn them.

These are the current criteria that I look for, but I continue to tweak based on outcomes. Very similar to the ideas in The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande, keep monitoring progress at various stages, and correct your selection criteria as you need to.

Best of luck in finding your projects. Stay tuned for more in this series.

***

This article is part of my upcoming workshop at the Lean Startup Conference. It’s on October 23, 2019, in San Francisco, where entrepreneurs and innovators from around the world will be gathering to discuss the latest innovations in modern management. You can use the code “Essey2019” for a discount on registration.

If you found this helpful

If you found this useful, I’d appreciate it if you would:

- Subscribe to receive the follow-ups.

- Share if you know someone who can use this.

- Comment with questions and stories.

We’re all in this together!